You are what you wear

Wearable products could bring medical monitoring to the masses but, as Steve Rogerson found out, a clash between consumer and healthcare cultures is looming.

Products that monitor the health of their wearers are becoming more popular, with people keeping a check on how many steps they have walked, their heart rate, body temperature and so on. But so far most of these products have been for the so-called wellness market, recreational activities that let people track their vital statistics for their own amusement. They are entertainment.

But that may be changing, with demand mounting behind wearable technology to evolve to more serious medical applications that doctors and other medical professionals can use to keep an eye on patients with problems. This does, however, look set to lead to a serious clash of cultures and regulations.

At present, most of the wellness type products are based around smartphone technology. Here, time to market and cutting costs are major drivers. The attitude often is let’s get it out there and, if there are bugs, people can download an update to fix them. Compare this with the medical device industry, where products have to go through months and sometimes years of testing before they can be given a stamp of approval to be used in earnest. More than that, different countries and regions around the world have different medical standards that must be met and a product that is OK to use in the USA may not be acceptable in Germany, or vice versa. These two worlds are on a collision course as it is the smartphone style technology that will be needed to bring wearables to serious medical applications.

“This is a very diverse market,” said Sylvain Gardet, Business Development Manager at Freescale. “There are consumer apps for sickness and wellness; we have the smart watch and the smart phone apps; there are embedded sensors in textiles; Google has the smart glasses. And now this is extending into new areas of healthcare, such as developments to help partially sighted people see better. This landscape is extending, and there are new companies emerging.”

But how are these devices to be regulated? Most healthcare devices have to go through a defined level of certification. “This is a long process and that is not compatible with the technology we find in our smartphone,” said Gardet. “It is usually a quite expensive process and not geared to technology being changed every nine to eighteen months. Medical products can need to have support available for fifty years.”

Kevin McDermott, Director of Marketing at Imagination Technologies, added: “We are going to need some legislation so that wearables can promise some degree of care if they are going to be used professionally. It will take some time to get there.” And David Andeen, Director of Reference Designs at Maxim Integrated, said: “The cultures of the two standards for consumer and medical will clash at some point. The quicker path to market is through the consumer side because they are not subject to stringent medical requirements. How that clash will play out, I don’t know, but we are heading for something like that.”

Doctors can already use a lot of the information coming from wearables to think about what they can do or identify a potential problem, but would need to use more established diagnostic methods to confirm what the readings indicate before deciding on treatment.

“There is a move for the likes of watches and bands to go beyond standard consumer applications such as pedometry, to more serious services such as measuring heart rate and blood pressure,” said Jim Davis, Senior Product Marketing Manager at Cypress. “There is a move towards more medical devices where doctors might start recommending people to wear them.”

His colleague at Cypress, Kendall Castor-Perry, added: “There is a tension between the consumer and medical side. Can you have devices that communicate with hospital and ambulance equipment? But you don’t want doctors to make decisions based on devices designed for consumer markets. The people who are making these watches are not making them for people who are unwell.” He said it would be a while before a device such as a smart watch would be reliable enough to give doctors the information they wanted.

However, a lot of the functionality, whether for professional medical equipment or consumer technology, is provided through software and it is here that the culture problem is at its height. Badly written software affects all areas – just look at the number of recalls in automotive, another area where professional and consumer technologies are clashing.

Soft solutions

“The answer is better software,” said Andrew Girson, CEO of the Barr Group consultancy. “The role of embedded software is increasing, so we need more well written software. A lot of people are still struggling with this. There are things such as static analysis and coding standards. These are basic things that mature software organisations will use and these need to be used more.”

One of the most common errors, he said, was a buffer overflow. This not only causes errors but can also form a pathway into a system for a hacker. “But if you use static analysis and coding standards, things like buffer overflows will be found before production,” he said.

David Hughes, CEO of HCC Embedded, believes the medical industry is already lax in the way it tests software compared with other safety critical industries such as aerospace, despite the existence of standards: “The medical industry has not adopted the standards,” he said. “The standards exist, but they have not been implemented rigorously. Such standards will have to apply to wearables as much as any other medical device, yet the medical industry already has problems trying to meet the requirements of safety.”

He said infusion pumps were a good example. Many do not meet the required standards but if the ones that didn’t were withdrawn lots of people would die. “But if you counted up the deaths caused by faulty infusion pumps, they would be taken off the market,” he said. “They are drip feeding us death, not in the way a failed aeroplane would.”

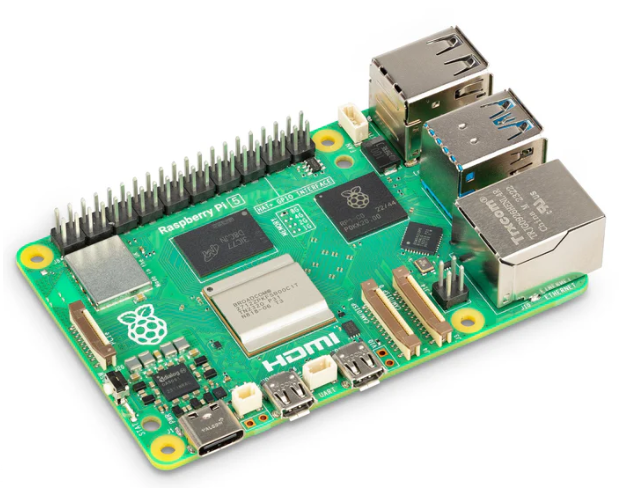

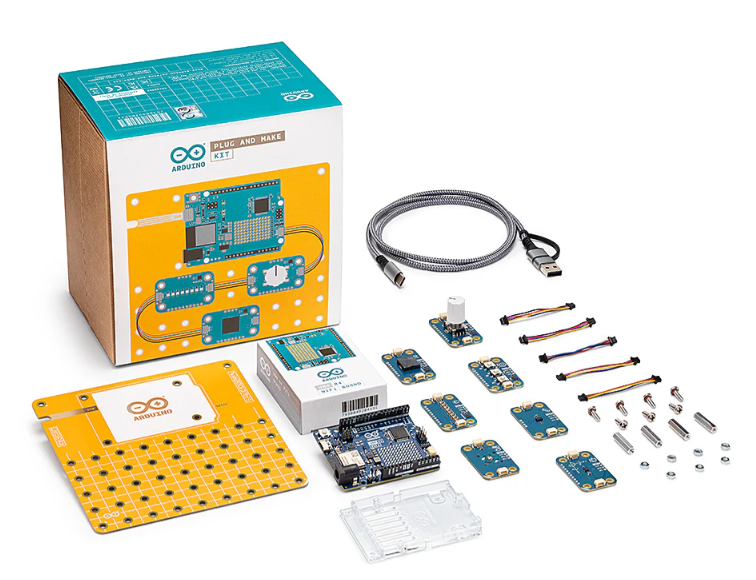

The other side of this equation is formed by new entrants to the market that have lots of clever ideas for what wearables can do but do not have the electronics engineering experience to put them into practice. Here, some companies are trying to lend a helping hand with reference designs and development kits. “These can help them develop a proof of concept,” said Gardet. “They can help them bring something to market with a minimum of knowhow.”

Communications

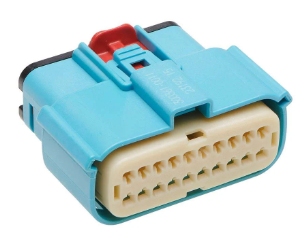

Bluetooth Low Energy seems to be winning the battle for the preferred communications technology, though Wi-fi is also popular, but medical wearables also have the problem of dealing with proprietary radio standards that already exist in medical equipment. This again could lead to a clash of technologies. “We need to look at how we can combine these two businesses of new communications technologies and proprietary radio,” said Gardet. “One protocol does not fit all so the combination of different wireless technologies is increasing.”

Andeen believes Bluetooth LE is an ‘excellent protocol’ for these types of applications because it consumes very little power and is being rolled out in millions of smartphones and other devices. “With communications, you need standards so they can be included in devices from different manufacturers.” And Castor-Perry added: “Bluetooth LE seems to be the only one that has a credible reach into both ends.”

Another aspect to all this is security. The data from the wearables will need to be encrypted both to protect others from gaining insight into an individual’s health and from hackers tampering with the way the wearables operate in a way that could affect someone’s health. “We might not want to share these data with everybody and we want to make sure that no-one can modify, say, someone’s heartbeat pattern,” said Gardet. McDermott added: “There is a lot of sensitivity in health data, so you need to control who looks at these data. And there is a health risk element as well.” Hughes also said the sensitive data could be used for political purposes, for example to point out a heart condition of a rival running for prime minister or president: “It all comes down to doing the job properly,” he said. “If you look at the security breaches over the past year, they have all been down to bad design and implementation. The protocols are very secure.”

Data analysis

A small sensor may be all that is needed to measure a person’s heart beat or the number of steps walked. But when thousands or even millions of people are wearing monitoring technology, there is a vast resource of data that could be used to gain insights into human behaviour. Such a volume of information has just never been available before, but those data need to be analysed.

“How are we going to cope if everyone is feeding back real-time information?” asked McDermott. “It is useful information, but how do we handle it? Also, how do you find the bits of data that you want?” Part of this, he said, would involve more intelligence either in the edge device or in the local gateway that could flag information that fell outside predefined limits: “Every heart beat of every person every second is a huge number that we can’t deal with,” he said. “It has to be processed in some way.”

Andeen added: “This is one of the major areas of research and development; the data science of gathering the massive amounts of data that will come from wearing these devices.” For example, Maxim has developed a reference design for galvanic skin response. “There could end up being millions of people wearing these,” he said. “With these and other wearables, there is an opportunity to mine a lot of data in regards to people’s health. It is a gold mine. Getting those data from millions of people rather than being a problem is an opportunity to understand the population a lot better.”

While technology for measuring the human body has existed in hospitals for many, many years, now with the advent of smartphones and wearables this technology is landing in the hands of consumers. One side-effect of this has been the technology used in the hospitals becoming cheaper but the downside is that such technology when bought over the counter does not have the backing of regulations and standards that ensure medical products are fit for purpose. Everyone seems to agree that the industry is heading for a crunch point, but not how the situation will be resolved.