Making wearable tech a reality

Despite the hype around wearable tech at the start of 2015, six months in to the year, mainstream adoption of wearable tech remains slow. Smartwatches, whilst widely available on the market, continue to be viewed as a smartphone peripheral, rather than a product in their own right. Meanwhile, Google’s high-profile Glass project has actually taken a step back, ending all sales of devices to the public.

Let’s not fool ourselves - at present, 2016 won’t be the year of wearable tech. By Simon Holt, Strategic Alliance Marketing Manager, element14.

Now, as we head into the second half of the year, it’s hard not to get a sense of déjà vu - multiple analysts are already declaring that 2016 is 'the year of wearable tech'.

The fact is there remain real, practical barriers to wearable technology that need to be overcome if we are ever to see widespread adoption. We at element14 have identified the four largest, which need to be resolved if the long-awaited 'year of wearable tech' is ever to come to pass.

1. Power issues

One of the most commonly cited challenges of wearable tech is the need for ever smaller, yet more powerful batteries and charging solutions. While battery life has always been a problem for portable technology, the need for wearable devices to be light and aesthetically pleasing has meant that the vast majority of traditional battery solutions are simply impractical. In the case of smartwatches this has proved particularly problematic, with most devices still needing to be charged on a near daily basis.

Given that insufficient battery life is widely considered the most pressing issue for wearable tech, numerous companies are already working to find a solution. One such solution currently being implemented is Bluetooth Smart, an ultra low energy standard designed specifically for use in small and portable IoT devices. By connecting via Bluetooth Smart, wearable technology can essentially offload some of its functionality onto a user’s smartphone, reducing energy consumption and extending the battery life of the device.

However, while such developments could one day remove power consumption as a barrier to wearable tech, they remain a long way off of widespread availability.

2. Over-reliance on smartphone ‘tethering’

As it stands, existing wearable devices differ from most technology in the sense that they do not replace their older alternatives. Whereas laptops came to replace PCs, and mobiles eventually replaced landlines, most wearable devices have been positioned as 'add-ons' to mobile phones, rather than their alternative.

In part, this is due to the fact that the components needed to mimic the functions of a smartphone are still considerably too large to be used within a wearable device. As a result, most smartwatches, headsets and fitness trackers all require some form of 'tether' connecting them to either a smartphone or a related tablet app. This dependence on additional devices remains a significant barrier in the minds of consumers, with many wondering why they should invest in a second device in order to achieve the same functionality as their existing smartphone.

As the number of these devices on the market increases, technology providers have to work ever harder to convince customers that their products add value. As it stands, however, many smartwatch manufacturers have struggled to demonstrate this value, offering their products instead as 'aspirational' purchases.

3. Lack of concrete standards

In order for wearable devices to truly meet their potential, they need to exist as part of the wider IoT ecosystem. As a result, they need to be able to communicate with both Internet services and devices that exist in the local area. This is an extremely complex task - to ensure power efficiency, wearable devices need to know not only when to communicate with other devices, but also when not to.

For every new device that is added to the wearable market, the number of necessary connection points has to increase, ultimately increasing the overall density of the network. With the global market for wearables expecting to reach 126m units by 2019, the potential for device interference becomes ever more difficult to manage.

This issue is also added to by the fact that existing UHF standards such as Wireless HD and WiGig are not designed to support such a huge array of connections. As a result, in order for wearables to succeed in the mainstream market, a more up-to-date standard (such as ECMA 387) needs to be adopted.

4. Issues of social acceptability

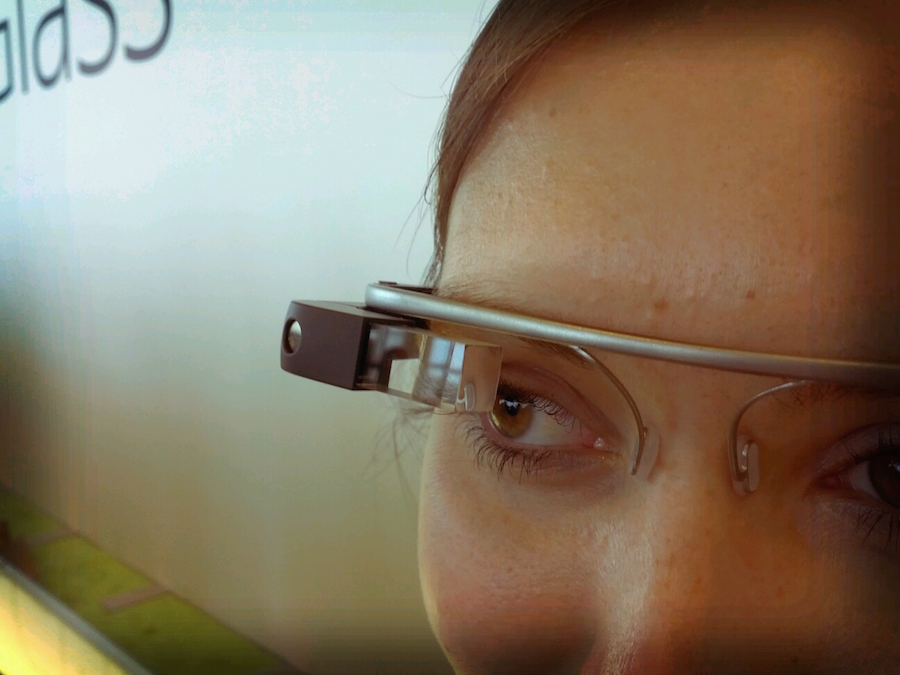

In addition to technical limitations, the wider adoption of wearable technology has also been slowed by a number of social considerations. The most infamous example of this was Google’s Project Glass, which received numerous complaints and legal challenges, ultimately being banned in banks, casinos, workplaces and restaurants.

In addition to these, the project also faced several political challenges, with US authorities ruling that users would be banned from wearing the headset while driving - further limiting the devices’ mainstream use.

While the social implications of wearable technology have been widely discussed, the only way that consumers will overcome such concerns is by using these products and expanding their social acceptability over time. Unfortunately, the establishment of these social norms is usually an extremely slow process, further holding back the advancement of wearable tech.

Engineers are, of course, working hard to counter each of these challenges we’ve identified. The more straightforward technical issues - in particular problems with power and industry standards – are ones that we hope, in time, they will be able to resolve. However, the more abstract concepts like social acceptability are much more long term, with an unclear route to resolution.

As a result, it’s consumers that will likely set the final date for the 'year of wearable tech', rather than any technology company. By resisting the development of smartglasses and other wearables many deem ‘invasive’, consumers are setting the standards for how wearable tech can and cannot be used. Only when the public have come to some degree of consensus on these concerns will wearables see mainstream adoption.