Paving the way to an energy efficient future

There are two key facts to consider when it comes to British roads. Firstly, in 2015 the total road length in Great Britain was estimated to be 245.9 thousand miles. Secondly, roads are only occupied by vehicles 10% of the time. This results in a huge amount of empty space which has the potential to be much more useful.

Across the channel in France, Colas, part of the telecoms group Bouygues, has constructed what it claims to be the world’s first solar panel road in a small Normandy village. The ‘Wattway’ consists of 2,800 square metres of electricity-generating panels and was officially opened last month by France’s Minister of Ecology, Ségolène Royal. The road will be trialled over the next two years to see if it can generate enough energy to power street lighting in the village of 3,400 residents.

The company claims that 20m2 of Wattway panels can supply the electricity requirements of the average home and that a 1km stretch of Wattway road can provide the electricity to power public lighting in a city of 5,000 people.

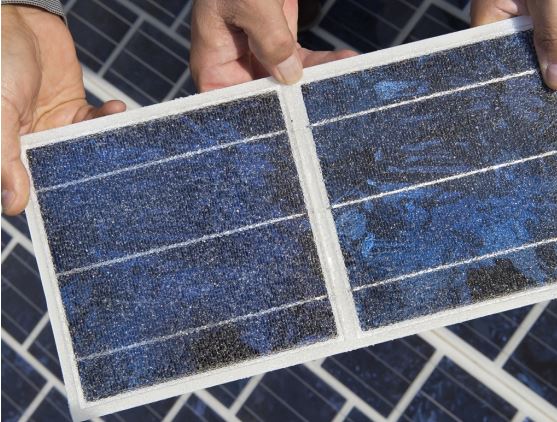

For those worrying about the meeting of traditionally delicate photovoltaic cells and heavy goods vehicles, never fear. Wattway is composed of cells inserted in superposed layers that ensure resistance and tire grip. The thin composite material can adapt to thermal dilation in the pavement as well as vehicle loads.

During 2015’s COP21 United Nations Conference on Climate Change in Paris, Colas was awarded a Climate Solutions Award for the Wattway Solar Road, signalling it as one of the best current solutions for alleviating and/or adapting to climate change.

On paper, Wattway seems like a solution to our ever-worsening climate crisis. However, the project has received criticism. Firstly, studies have shown that PV panels laid on flat surfaces are less efficient than those placed on sloping surfaces. Additionally, the Normandy road cost the public €5m, and critics argue that this could be better spent developing measures which are more certain to work.

Marc Jedliczka, Vice President of Network for Energetic Transition (CLER) told Le Monde: “It’s without doubt a technical advance, but in order to develop renewables there are other priorities than a gadget of which we are more certain that it’s very expensive than the fact it works.”