What technologies will emerge as leaders for industrial sensors?

The use of industrial sensors is expected to grow as part of the IoT, but there is little agreement on the technologies that will be used. Steve Rogerson reports.

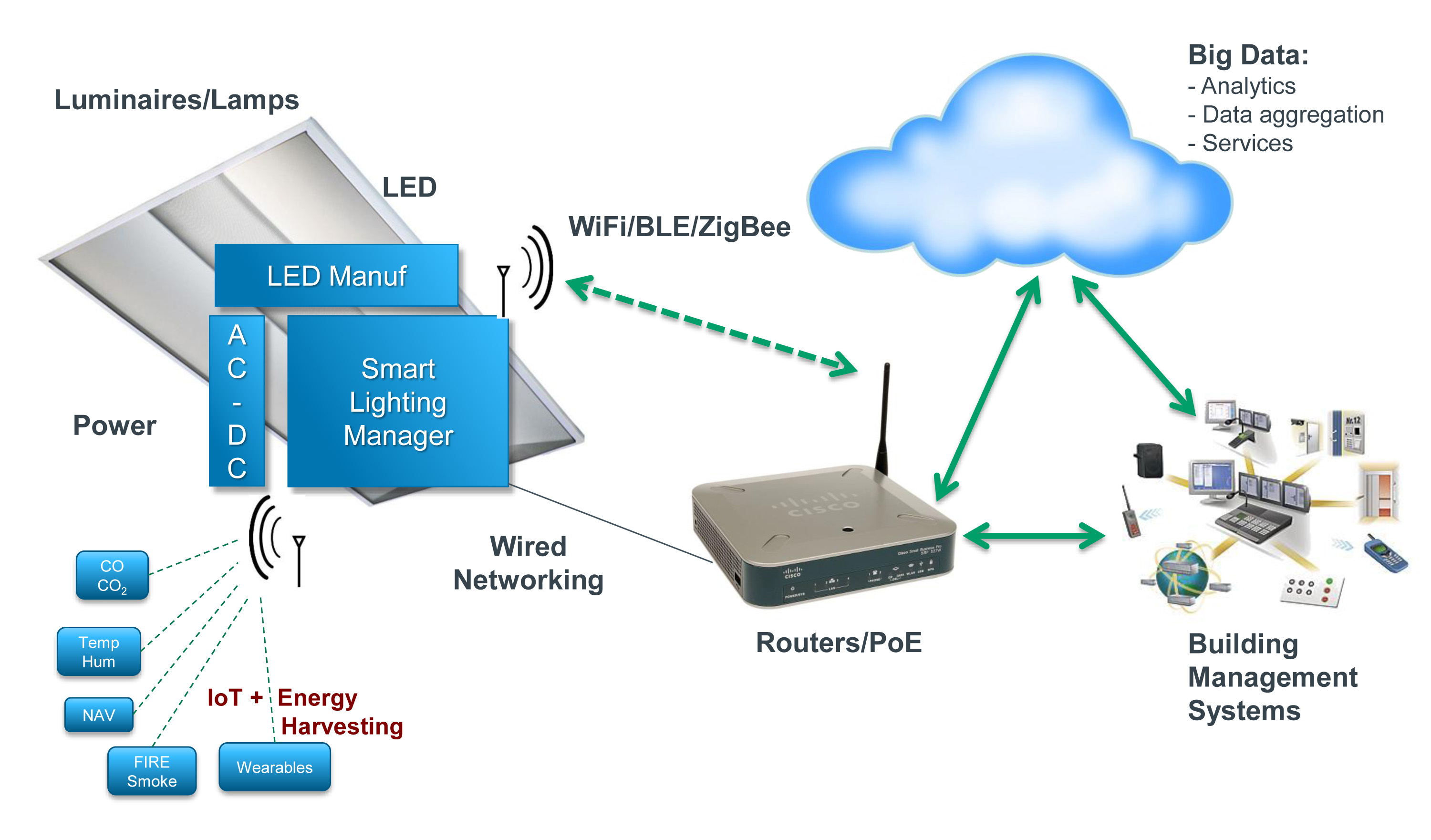

One of the main planks for the expected growth of M2M and IoT is the predicted increase in intelligent sensors in the industrial sector, where they will provide insights in to what is happening on the shop floor, will help in making and actioning decisions, and feed back information to a central processing unit to give a more accurate view on the factory’s activities. However, there is much disagreement among companies on how best such a network could be deployed. There are even arguments about whether wired or wireless is the way to go, the network architecture and where to put the processing hubs.

The result of all this, at least in the short term, is that different installations are going to go different ways and there will be a mix of installed systems. This could also hold back wide-scale deployment as potential users wait to see how others manage before deciding on their own set-ups.

Early adopters are likely to include those working in hazardous environments, where they already have some remote monitoring due to the nature of their business. Moving up to a more intelligent sensor network is not such a large step.

“In harsh and hazardous environments, it is critical to find out what is going on,” said Sajol Ghoshal, Vice President of Strategic Development at ams. “Sensors need to be smaller with local intelligence to make decisions to adapt to the environment,” adding that a dumb sensor sending information back for processing could be difficult because of EMI. “That is why you need local intelligence,” he said. “So you have a sensor or multiple sensors with a small, little micro as the brain.”

Wired versus wireless

One of the big debates is whether to go for wired, wireless or a combination of the two; a moot point still, but some vendors are dead set on one or the other. Ghoshal is firmly in the wireless camp: “You need a way to communicate with the sensors,” he said. “You don’t want wires, you want wireless.”

However, even he admits in some areas you are forced to use wires. “If you look at the oil and gas industry, they send wires down with the drill, so they use wires anyway. But in an industry with lots of machines and robots, the harshness comes from EMI and there are methods to overcome this with wireless.”

Wireless still has problems, such as multi-path fading where the signal is reflected off various surfaces; the original and reflected signals can arrive out of phase with each other, thus cancelling out the signal. If equipment or vehicles are moving around the factory the situation can become worse, as they can cause temporary blockages or reflections.

Many networks will use a mixture of technologies

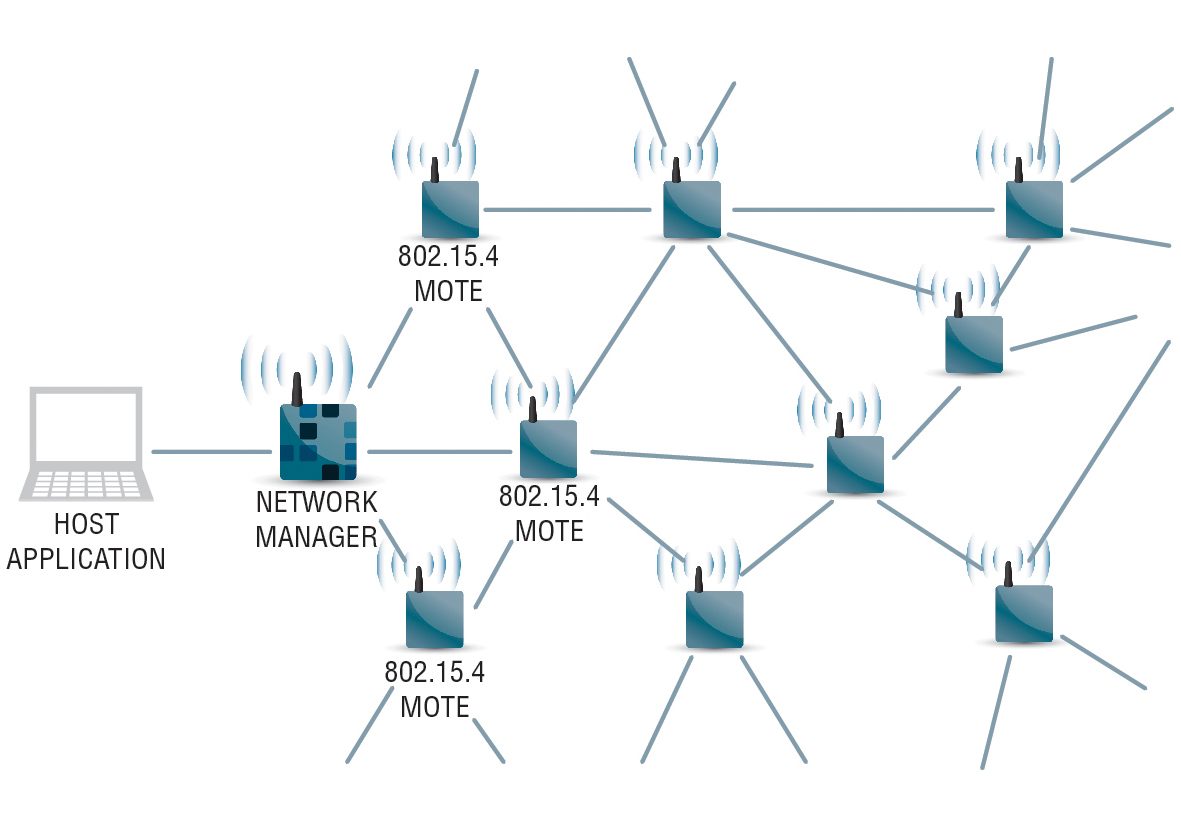

Ross Yu, Product Marketing Manager with Linear Technology, sees channel hopping as the answer: “If you have a network with several points, it is almost impossible to find a single channel that will work,” he said. “But if you can cycle through the channels, you can almost always find one or more channels that will work.” Ghoshal said techniques such as CDMA, where the signal is dispersed across a large spectrum, means that interference in one area won’t disrupt the signal. This does, though, mean a more complex receiver. Here, the driving force is not large volumes of data, as it is in other areas, but small packets over sometimes long distances. The system also needs to be adaptable to changing requirements. Bluetooth Low Energy is now being seen as a viable communications technology for many of these applications, and that has the advantage of being able to communicate with smartphones or tablets for monitoring and control purposes. This is a point-to-point system but there is work being done to make it act as a mesh network. Marc Pegulu, Vice President for Wireless and Sensors at Semtech, thinks mesh networks generally consume too much power and are a lot harder to deploy and manage. He prefers a star network where the nodes communicate directly with the centre. “It is a much simpler protocol,” he said. “It is cheaper and more battery efficient. And it is much more scalable.”

Jacqui Adams, Director of Product Management at XMOS Semiconductor, commented: “The feedback from our customers is that they do not think wireless is robust enough for the data to get through,” she said. “They only want wireless where it is difficult to lay new wire, such as at the top of a chimney or where you need sensors on a mobile platform. Generally, they are not convinced that wireless yet solves their problems. They see it as something for the future.” Adams said the best set up in most cases was to have a local intelligent hub connected by wire to various sensors; this could react quickly to changes in the environment. The long-term data, for which time is not as critical, could be sent from that hub to the central processing unit. “Some customers want a log of the information in the background, but there is no reaction time needed for that,” she said. “It is just for storing data. Others just want a flag for event changes.” Such a system, she said, would also remove a single point of failure. The local hub could have multiple cores each handling a different sensor. If one failed, the job could be taken over by another. “If everything goes back to one CPU, then that is a single point of failure,” she added.

The other advantage of a distributed system is that it is easier to expand. If everything works through a central processor it needs to be taken down to add more nodes, but with a distributed system only the part that is being extended needs to be taken down. The same situation happens with a fault in that it only takes out part of the network. “You do need to rethink how you organise the system,” said Adams. “People have been used to processing power going up and up and up. This changes with distributed control. But the system architecture can be more complex and needs to be thought out in advance.”

Pegulu thinks that generally a wired system would be too expensive but acknowledges that in higher bandwidth applications it may be necessary: “Every time you do anything wired, it is more costly,” he said. “And you can’t run wires to a lot of existing structures. It is expensive and costly to deploy. But if you are thinking about video for security or monitoring, it is unlikely you will go wireless because of the bandwidth and reliability.”

Schematic of a mesh nework

What is essential is that the sensors consume little or no power. They will have to survive in harsh environments for years and nobody wants to have to replace batteries every few months; doing so with the shut down that would be involved could even negate all the advantages. The question therefore is how to get energy to the sensors so they are not reliant on a battery. One option is to use the method of communicating with the sensor to also provide the power. Another is for the sensor to harvest energy locally, such as from machine vibrations or light. The power consumption in many sensors has been driven down to microwatt levels, but transmitting data is what drives the consumption higher. Therefore if it is harvesting energy during non-transmitting times it also needs the ability to store that energy to use when it is transmitting.

This leads Pegulu to conclude that energy harvesting is too complex and thus too costly at the moment for mass deployment: “The technology is much too expensive,” he said. “In the future, it will be viable if they can reduce the cost. But a lot of innovation is needed to reduce that cost.”

One of the drivers for growth in the IoT will be sensor networks, but to what degree? As Ghoshal put it: “The Internet of Things is going to be bigger than anything.” However, Pegulu believes cost is holding people back. He said: “We are seeing more requests from industrial companies who want to connect sensors but do not have the right level of investment.” But Ghoshal believes that economies of scale will eventually overcome this: “Sensors will be in the billions and that will drive down the cost. This market will explode.” And Pegulu agreed there is a pick up but thinks it will be the second half of next year before there is significant growth. “The guys who are already using wireless connectivity in their factories are leading the way,” he said. “They are now coming through. We are seeing a lot in the fuel area for monitoring levels in fuel tanks so they know when to refill them or change the tanks.”

As for other applications, it seems unlikely at least in the short to medium term that there will be any technology winner in industrial sensor networks. But if the market is as big as some are predicting, then there could be more than enough business to keep everyone happy.