Metering faces the costs of being smart

The smart meter market is awash with different standards and technologies and, as Steve Rogerson found, there is little sign of any light at the end of the tunnel.

The roll out of smart meters looks set to begin in earnest for many countries over the next five years, but the situation is a bit of a mess, with different countries and even different utilities within those countries going their own way in terms of how the meters work and, just as importantly, the way those meters will communicate over long and short distances. And these problems are not going to go away. Given the high cost of replacing meters, the aim is for the meters to have an installed life of the order of 15-20 years. This means at least a couple of decades are likely to pass before any agreed standards on smart metering will result in some sort of unification in the market. This is also going to find little favour among consumers, who are used to updating technology every couple of years. The early takers for smart meter programmes will be seething five or so years down the line when they see their neighbours getting the latest models while they are locked in to an older model for another 15 years at least.

On top of all that, this disjointed market makes little financial sense as it is difficult to achieve the economies of scale that are needed to drive the costs of the meters down to more acceptable levels. True, some are getting round this by allowing more updates via software and effectively over-designing on the communications side by giving the meters the ability to work with different wireless standards. Some are even going down the software-defined radio route.

“There is some standardisation,” said Jean-Marc Darchy, Business Development Manager, Freescale. “But it is still an important political game. There is still a legacy of all the contributors to the programmes as regards when and what is going to happen.” Part of the problem is the differing geographies that make up the countries. For example, for remote farms and houses in a rural environment, it might make more technological sense to have the communications using existing cellular networks given the distances involved, but the cellular networks are notoriously poor in some rural areas, which will mean more investment in base stations. “Who is going to pay for a base station for one or two farms?” asked Olivier Amiot, Marketing Director, Sierra Wireless.

In urban areas, it may make more sense to use optical fibre or have local hubs and use a short-haul communications standard to link them with homes. Given short-range radio will be used in many cases within the home, this has its attractions. But there is not even agreement on the best way to link the homes in neighbourhood area networks, with proponents of both mesh and star topologies.

“The advantage of star topology is it is better suited to battery operated devices,” said Jon Lewis, Operations Director, Senaptic. “With a mesh network, each node has to relay messages, so that means each node will have more traffic and its receiver has to be on all the time. For electricity meters with their own power, that is not so much an issue, but for battery-powered meters it is.”

There is even a debate on whether it is the meter itself that connects to this network or whether the meter connects to a separate device in the home and through that to the neighbourhood network. “No one solution will fit all the cases,” said Amiot. “It will be very difficult to find one solution. There is nothing that suits everyone.”

Another problem crops up in urban areas for the short-haul transmissions with the different types of housings and blocks of flats causing particular headaches. “Small houses are relatively easy to cover,” said Lewis. “But blocks of flats can have all their meters in one room on the ground floor and you have to go up through several floors to get to the displays in the flats. One way is to use powerline technology, but that is more expensive. The other is to use a sub-gigahertz version of Zigbee and that is being defined, but flats will still be the most difficult to cover.”

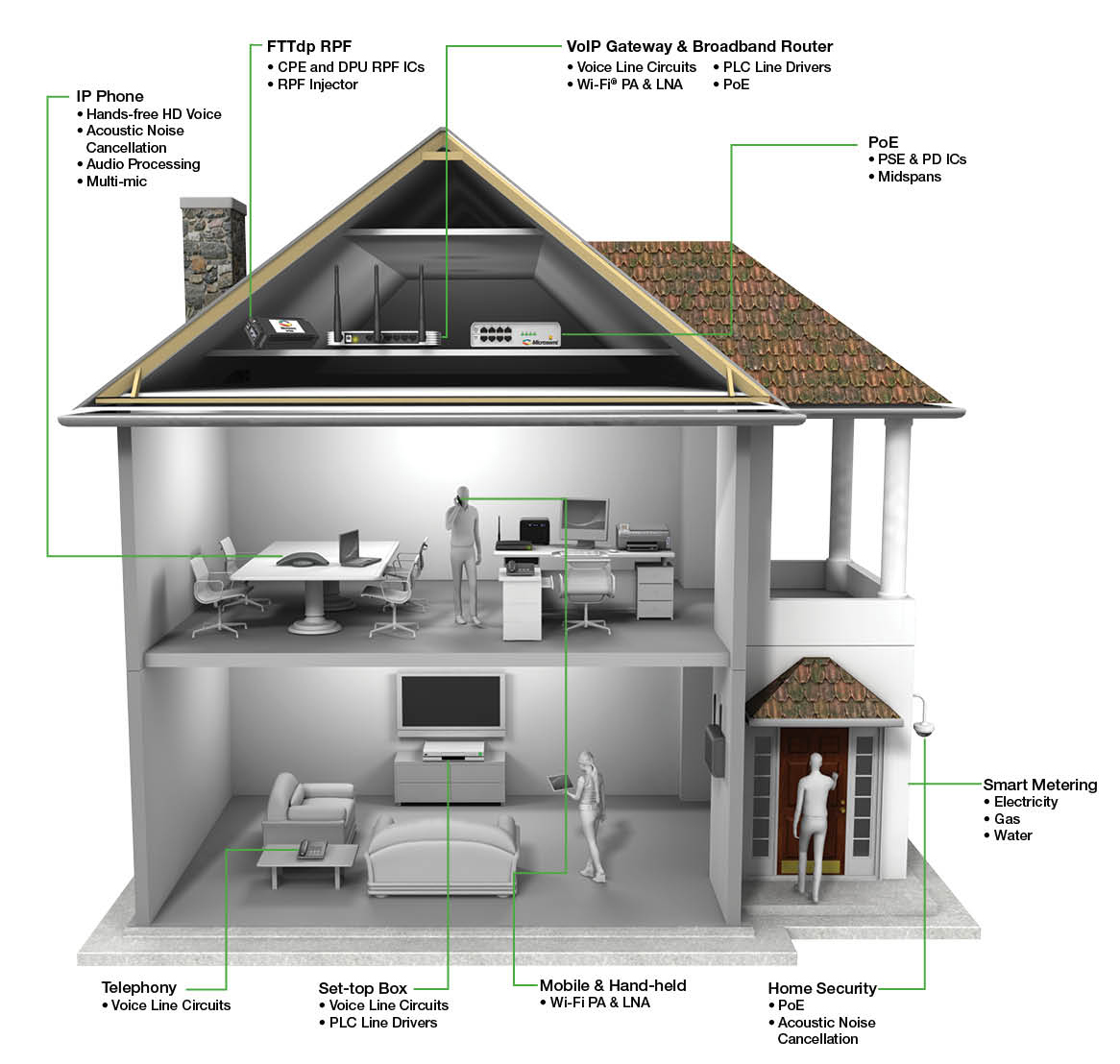

The problems are exasperated because in a connected home the different meters – water, gas and electricity – may also need to communicate with each other and maybe with a central hub, which brings with it questions of interoperability. “Each region is picking a different frequency,” said Vivek Mohan, Senior Product Manager, Silicon Labs. “You need true integration with different vendors’ meters talking to each other. This can be quite difficult.”

Security

One of the major concerns with smart meters is security. This comes in two forms. First, there is a need to protect the meters in the home from tampering, to make sure people don’t work out ways they can fiddle the meter to reduce their bills. The second is security on the grid itself, to protect against malicious hacking that could bring down the electricity network.

“There are also concerns about the data being used to learn about the use habits of people,” said Jim Aralis, Chief Technology Officer, Microsemi. “People can see this as an invasion of privacy, especially if the smart meter is talking with your appliances in a connected home.” Even though some of these security risks may be remote, Aralis still believes they need to be taken seriously: “With a meter, the potential of stealing an operator’s power is there,” he said. “But it is not huge. For the network, you need multiple levels of security to stop people turning off the grid or overloading it. You need hardware and software to stop this.”

In home networks, there will also be different security requirements at different parts of the network, which will make the communications trickier. “People talk about common security between, say, a thermostat and the smart meter,” said Mohan. “But the security requirements of these devices are less than what the smart meter needs. It comes down to what the consumer will pay. They are not going to pay a lot for a door or window sensor. If they are too expensive, they will not be viable. So, do you need the same level of security in home automation? That is a big question and people are arguing both sides of it. I think in five years we will have a common security protocol for this.”

The other problem on the meter side is the security has to be good for the life of the meter, which as said could be 15 to 20 years, or maybe longer. But David Hughes, CEO, HCC Embedded, believes the security that is available today is good enough: “Very few algorithms have been cracked in recent years,” he said. “Most of the hacks have been down to poor coding standards rather than the algorithms used.”

He said that as long as people used higher coding standards, there would not be a problem: “The communications side is not a problem as the bandwidth is very small,” he said. “The issue is to build a secure and clean system.” He also said the meter makers needed to invest in secure and reliable flash memory so this would continue working for the life of the meter: “Flash by its nature is quite unstable,” he said. “We have done work to make it last a long time. To get the reliability, you have to invest.”

Costs

The main goal coming from governments and utilities is to bring down the price of smart meters. The installations themselves are going to cost a fortune, so any savings that can be made with the meters will be more than welcome. “The goal for a lot of companies like us is to find an innovative approach to reduce the cost,” said Freescale’s Darchy. “We are looking at things like having single chips that will do both the measurement and communications. Only very recently, in the last 12-18 months, have standard MCUs been developed with the speeds to handle the stacks in real time.”

He said the meter market was getting close to what happened with mobile in that there would be software-defined meters: “Everything is running on software,” he said, “so you can change this quite quickly with a software update. Most of the MCUs will be running on ARM cores, so they will not depend on proprietary DSPs or hardware accelerators. It can be done on a standard MCU.”

Aralis thinks the metering and communications chips will stay separate for some time, mainly due to the lack of standardisation: “There is no standardisation on communications, so putting them together creates too many variables,” he said. “But as we standardise this will start to happen at least on a country level. The technology is there to put everything on a single chip and make it more economical; the problem is standardisation.”

Mohan added: “When you design these products, you make them really flexible to support different requirements and load whatever software stack is needed. We have a common hardware platform for whatever software is loaded. Most semiconductor vendors do not have the luxury of producing different ICs for each region. That is an expensive way to do it.”

He pointed out that this was really a software-defined radio approach to let the chips be used with different networks: “This means you can load Zigbee, WiFi or a Wireless Mbus stack onto the same hardware.”

Amiot believes the answer to the cost problem is to simplify everything: “Technologies such as LTE are high speed and high bandwidth,” he said, “but for this type of M2M application you need low power and low bandwidth, and that can drive cost massively down. You can get rid of all the unnecessary silicon and be more like the 2G model.”

The smart meter programme will have the difficulty of still being in the development phase as it is rolled out and some of the early adopters are going to find problems that have not yet been considered. “There will be lessons learned from the initial installations,” said Darchy. “There will be some surprises and difficulties to overcome. No country is the same and each will have their own issues. For example, the noise on the networks will be different because they have been designed differently.”

The key, he said, will be being able to adapt quickly to these discoveries: “We are not just going to be able to ship something and have it work in every case,” he said.