IoT privacy - included as standard?

Lack of privacy is not a “user issue”; it’s an engineering fault. When it comes to the Internet of Things, individual privacy is at the top of the agenda for both consumers and the wider media. For engineers and product developers however, it is rarely seen as the number one concern... By Simon Holt, Strategic Alliance Marketing Manager, Farnell element14.

For the most part, this may be due to the wide variety of issues that engineers already have to consider when producing their own internet-connected devices. Between the development of IoT standards, the selection of wireless technologies, and the adoption of an appropriate Internet Protocol, most engineers are still wrapped up in the basic infrastructure of IoT. As a result, more abstract ideas such as personal privacy can quickly fall by the wayside.

It can be all too easy for design engineers to consider privacy as an afterthought. But the truth is that if designers want the IoT to succeed and become widely adopted, they need to start building privacy considerations into designs from the ground up. Waiting for legislators to impose demands from above is only going to slow this down.

The media hype promoting the virtues of IoT to consumers is fast dissipating to make way for an increasing focus on how technology is storing, using, and securing private information. Recently, element14’s own research has shown that as many as 64% of consumers are concerned with how wearable technology will impact on their privacy.

Whether these concerns are justified or not, it is hard to deny that the IoT is fundamentally changing the way technology collects and uses our personal information. By seamlessly embedding billions of sensors and connected-devices into everyday life, the amount of data being stored is inevitably going to increase.

This represents a significant privacy concern for a number of reasons.

Firstly, as the quantity of data increases, the harder it becomes to control. Monitoring and securing one point of data collection may be easy enough, but as the IoT expands to include 20bn interconnected devices, data security becomes a far more complex issue. While there are already multiple security standards currently being developed to address this concern, it is the designers and engineers that will need to find a way to implement these standards without damaging the end-user experience.

Secondly, in order to maximise the long-term usefulness of the IoT, multiple devices will need to communicate with one another, regardless of ownership. As one example, a connected car might need to link with an individual’s mobile phone or smartwatch. At the same time however, it may also need to connect with other cars on the road in order to gather relevant traffic information. With information being borrowed from multiple different individuals and sources, the idea that any one individual ‘owns’ their data becomes increasingly difficult to impose.

Once again, this presents another challenge for engineers and product designers to overcome. While the collection of data is vital for the IoT to function, designers need to ensure that their products and services do not harvest any more data than is required to carry out a particular task. At the same time, this data needs to be stored securely and should never be shared without the express permission of the original owner.

As these examples make clear, personal privacy has increasingly become a ‘design’ issue. And yet, the problems surrounding privacy are still largely being framed from the perspective of the consumer, with the onus being placed on the user to ‘protect’ their own data.

This focus may be due to the fact that most technologies that collect user data have previously only existed online (search engines, social media, etc.). These tools exist in an abstract form, outside of the physical world. As a result, many of the traditional ways to protect personal privacy no longer seem to apply. In the instance of social media, most online services request personal information as part of their core function. In these instances, it is all too easy to ‘pass the buck’ onto the consumer, suggesting that if privacy really meant that much to them, they wouldn’t be uploading personal information to social networking sites.

The IoT is shifting this debate back into the physical realm. By helping to make privacy a more tangible issue, IoT technologies are increasingly colliding with the social norms of the ‘offline’ world.

Consider the wearable technology project, Google Glass. While the concept of search engines retaining user-data seemed too abstract to directly offend, the idea of wearing a video camera suddenly provided a tangible dimension that brought the issue of privacy to life. Now, following an initial trial period, Google Glass has been banned in cars, cinemas, banks, casinos, hospitals and restaurants around the world. This backlash represents a very real issue, and one that IoT designers need to be conscious of and actively address.

With privacy back on the agenda in a very real and tangible way, the onus on data protection is shifting away from consumers and back to the products themselves.

As IoT technologies start to penetrate every aspect of our lives, the days of “don’t like it, don’t use it” have long since passed. Instead, if IoT is to succeed, we must give customers confidence that the products and devices being developed are safe and that their data is secure.

While some of this can be achieved through strong marketing messages, at the end of the day, perhaps the best way to address customers’ concerns is to place privacy at the forefront of your product from the very outset. Rather than expecting customers to ‘protect’ their own privacy, we should be providing them with devices that do everything possible to avoid putting that privacy at risk.

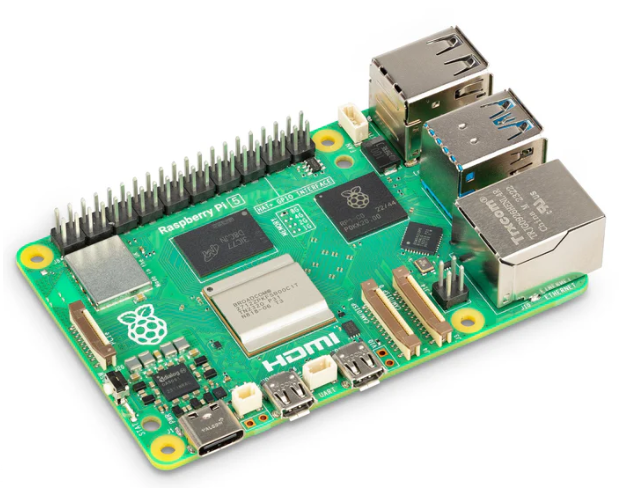

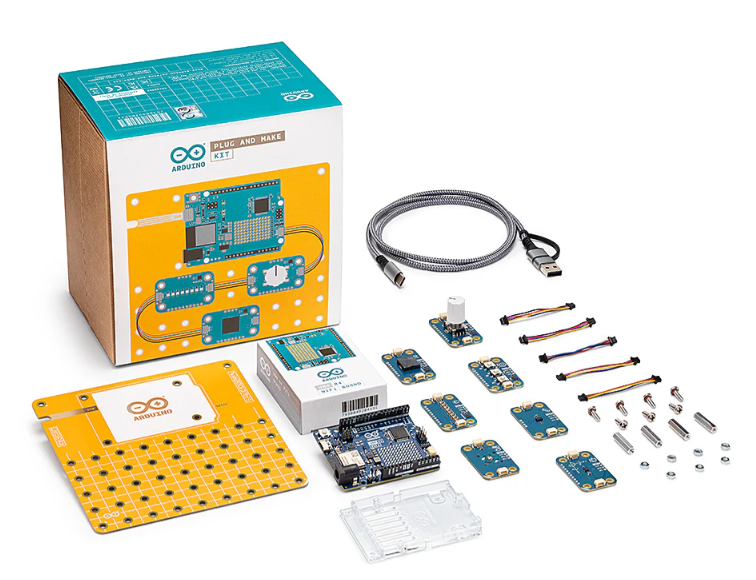

This is a serious challenge for engineers and developers to overcome, but it is one that is already being addressed across all levels of the development of the IoT, from hobbyists to professional engineers. By including privacy protection ‘as standard’ designers are not only helping to put consumers’ fears to rest, they are also providing a more stable infrastructure for the IoT - and a strong platform for widespread adoption.

Telling engineers that they need to increase their focus on privacy is one thing, but the reality of how to achieve this is a far more complex matter. While there is no one solution to ‘fix’ the issue of privacy, one of the best places for engineers to start is in attempting to ensure that all IoT devices conform to the Fair Information Practice Principles (FIPPs). Originally set out by the US Federal Trade Commission, the FIPPs have become a go-to standard for safe guarding privacy online.

They include:

- Notice – Ensuring consumers are made aware that their information is being collected.

- Choice – Providing users with the ability to opt-out of data collection.

- Access/Accuracy – Allowing users to view the information collected and to verify or contest its accuracy.

- Data Minimisation – Never collecting data unnecessarily or retaining it for longer than is required.

- Security – Protecting all collected information from internal and external privacy breaches or threats.

While these FIPPs provide strong guidelines for designers and engineers to follow, their application does prove challenging. For example, while increasingly user-friendly privacy controls are being bundled with most new technologies, it is far harder to imagine how this would work with IoT sensors or so called ‘smart dust’. For many IoT devices, it would simply not be possible to ask permission at every instance of data collection.

The same is also true of the process of data minimisation. While it is important to avoid storing data over long periods of time, the more retrospective information that is available to each individual device, the more intelligent the Internet of Things will become.

As these few examples make clear, the FIPPs do not necessarily provide a solution to all IoT privacy concerns. What they do provide however is a useful set of guidelines for engineers to keep at the forefront of their minds. This will ultimately help us to determine the right balance between protecting privacy and providing a high quality user experience.

While some of these decisions will still fall to governments and industry bodies, many of them are already being faced head-on by designers and hobbyists from all around the world. This is what makes the IoT such an exciting topic for those within the design community - not only anticipating the benefits, but also overcoming the challenges.