Researchers solve the mystery of cement’s structure

Concrete is the world’s most widely used construction material, so abundant that its production is one of the leading sources of greenhouse gas emissions. Yet answers to some fundamental questions about the microscopic structure and behaviour of this ubiquitous material have remained elusive.

Concrete forms through the solidification of a mixture of water, gravel, sand and cement powder. Is the resulting glue material (known as cement hydrate, CSH) a continuous solid, like metal or stone, or is it an aggregate of small particles?

As basic as that question is, it had never been definitively answered. In a paper published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, a team of researchers at MIT, Georgetown University and France’s CNRS (together with other universities in the U.S., France and U.K.) say they have solved that riddle and identified key factors in the structure of CSH that could help researchers work out better formulations for producing more durable concrete.

Roland Pellenq, a senior research scientist in MIT’s department of civil and environmental engineering, director of the MIT-CNRS lab <MSE>2 hosted by the MIT Energy Initiative and a co-author of the new paper, says the work builds on previous research he conducted with others at the Concrete Sustainability Hub (CSHub) through a collaboration between MIT and the CNRS. “We did the first atomic-scale model” of the structure of concrete, he says, but questions still remained about the larger, mesoscale structure, on scales of a few hundred nanometres. The new work addresses some of those remaining uncertainties, he says.

A bit of both

One key question was whether the solidified CSH material, which is composed of particles of many different sizes, should be considered a continuous matrix or an assembly of discrete particles. The answer turned out to be that it is a bit of both - the particle distribution is such that almost every space between grains is filled by yet smaller grains, to the point that it does approximate a continuous solid. “Those grains are in a very strong interaction at the mesoscale,” he says.

“You can always find a smaller grain to fit in between” the larger grains, Pellenq says, and thus “you can see it as a continuous material.” But the grains within the CSH “are not able to get to equilibrium,” or a state of minimum energy, over length scales involving many grains and this makes the material vulnerable to changes over time, he says. That can lead to “creep” of the solid concrete and eventually cracking and degradation. “So both views are correct, in some sense,” he explains.

The analysis of the structure of hardened concrete found that pores of different sizes play important roles in determining the material’s characteristics. While smaller, nanoscale pores had been previously studied, mesoscale pores, ranging from 15 to 20nm on up, had been more difficult to study and not well-characterised, Pellenq says. These pore spaces can play a major role in determining how susceptible the material is to water that can enter the material and cause cracking, eventually leading to structural failure. (This cracking, perhaps surprisingly, has nothing to do with the expansion of the water when it freezes, however).

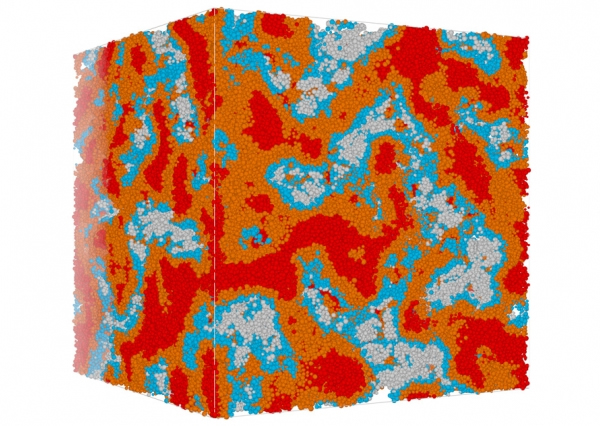

This image of a simulated concrete sample shows the 'packing fraction' which describes the fraction of the volume that is filled with solid material. In this case, the average packing fraction is 0.52. Colours indicate the variations within the sample, ranging from less than 0.4 to more than 0.64. The size of the cube is 0.6μm.

The new mesoscale simulations are the first that can adequately match the sometimes conflicting and confusing results seen in experiments measuring the CSH texture, Pellenq says.

Towards better formulae

The new simulations make it possible to match the values of key characteristics such as stiffness, elasticity and hardness, which are seen in real concrete samples. That shows that the modelling is useful, he says, and might help guide research on developing improved formulae, for example ones that reduce the required amount of water in the initial mix with cement powder. It is the manufacturing of the cement powder, a process that requires cooking limestone (with clays) at very high temperatures, that makes concrete production one of the leading sources of human-caused greenhouse gas emissions.

Fine-tuning the amount of water needed for a given application could also improve the material’s durability, the researchers found. The amount of water used in the original mixture can make a big difference in concrete’s longevity, even though most of that evaporates away during the setting process. While water is needed in order to make the slurry flow so that it can be poured in place, too much water leads to much bigger pore spaces and more loose, 'fluffy' regions in the set concrete, the team found. Such regions might leave the material more vulnerable to later degradation, or could even be designed to improve its durability.

Christian Hellmich, Director of the Institute for Mechanics of Materials and Structures, the Vienna University of Technology, who was not involved in this research, added: “This is a quintessential step towards the provision of a seamless atom-to-structure understanding of concrete, with huge mid-term practical impact in terms of material design and optimisation. This research helps to promote concrete research as a cutting-edge scientific discipline, where the cooperation of engineers and physicists emerges as a driving force for the reunification of natural sciences across the often too-tightly set boundaries of sub-disciplines.”

The first contributor of this work is MIT postdoc Katerina Ioannidou. The team also included other researchers at MIT; the University of California at Los Angeles; Newcastle University in the U.K.; and Sorbonne University, Aix-Marseille University, and CNRS, in France. The work was supported by Schlumberger, the French National Science Foundation (ANR) through the Labex ICoME2 and the CSHub at MIT.