Caution: inappropriate cable cleats

Across the electrical industry, the incorrect interpretation of short-circuit test reports leads to inappropriate cable cleats being specified and installed with worrying regularity.

Richard Shaw, Managing Director, Ellis, explains the situation and what needs to be done to rectify it.

The role of cable cleats in any electrical cable installation is of paramount importance. They are there to prevent costly and dangerous damage to cables and those around them in short circuit situations – in fact the only thing underspecified cleats do in a short circuit situation is add to the shrapnel.

At present, third party short-circuit testing is accepted as the best way to effectively prove a cleat does what it claims. Unfortunately, the validity of this process is being jeopardised by the fact that the headline figure on such reports is all too frequently taken to mean that the products tested deliver the same level of short-circuit withstand irrespective of the installation.

This is blatantly incorrect. You cannot say that a specific cable cleat has a short-circuit withstand of 150kA without qualifying the statement by putting it into context in terms of the cable size, cable arrangement and how often the cleats need to be spaced.

Take for example a recent report I was given, which had a headline figure that alluded to the product withstanding a peak short-circuit of 138kA. Upon full reading it became clear this was simply not the case. The test rig was set up with four trefoil circuits in parallel and while the overall fault level was 138kA, each of the four trefoil groups only saw a quarter of the fault, meaning they only withstood the equivalent of 34.5kA.

The ease with which this report could have been misinterpreted is clear, and if you imagine it being reviewed by an over-eager salesman and an ill-informed specifier it’s even easier to see a project being incorrectly specified.

Worryingly, if the product in question was installed on a system with a peak short-circuit over 34.5kA, just a quarter of the report’s 138kA headline figure, it would provide as much protection as a plastic cable tie.

This example is one of many and clearly highlights the need for third party test reports to be carefully studied. The best way to do this is to ask two simple questions. Firstly, is the product tested the same as the product being offered? Secondly, is the test installation similar to the project installation? If the answers are both positive then the product should be suitable.

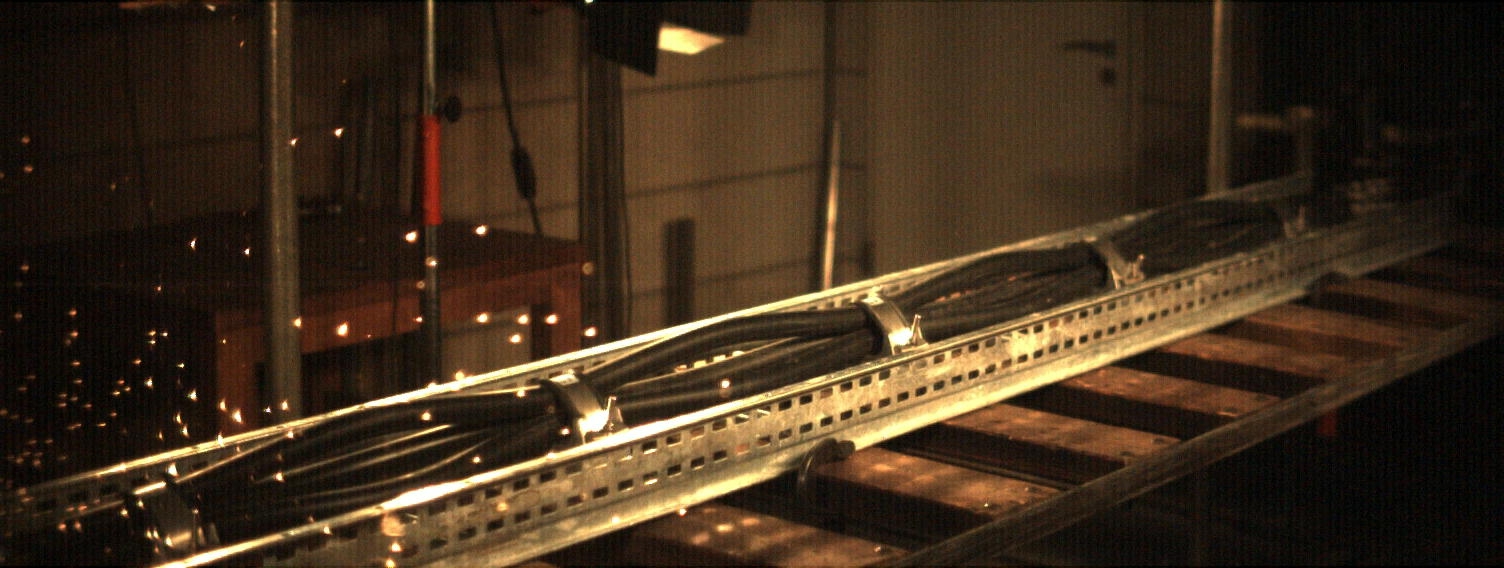

Cleat undergoing short circuit testing

If you want absolute certainty, then ask for a project specific test. This is third party testing at its most extreme and is the only way to guarantee that the cleat being installed is suitable for the installation.

It does need to be noted that the certificate this delivers is specific to the installation, its fault level, spacing and cable configuration. The reason for this is that a cleat’s short circuit withstand is only valid for a cable diameter equal to or greater than the diameter of the cable used in the test. So if the project in question ends up using smaller cables than those referred to in the test then the force between the cables is proportionally greater, meaning the certificate is inappropriate and the cleats will not provide the protection they are installed to give.

Ideally, project specific testing would be supported by the adoption of cable cleats as short circuit protection devices, which would automatically give them the same degree of importance as fuses or circuit breakers.

The argument for this isn’t as outlandish as it first sounds. In the event of a fault, the forces between cables reach their peak in the first quarter cycle, which is the point that cleats earn their crust. In contrast, circuit breakers typically interrupt the fault after three or even five cycles by which time, if the cleats are underspecified, the cables will be long gone.

It does seem that the process of overhauling attitudes towards cable cleats is far more difficult than it should be, especially when the simple steps of introducing project specific testing and adopting cleats as circuit protection devices would resolve every issue. And while I’m hopeful this will eventually happen, I’m realistic enough to know it won’t occur overnight. Until then, myself and everyone else connected with Ellis will continue to bang the drum for cable cleats wherever and whenever we are given the opportunity.”