Advanced lenses help in the hunt for dark energy

Since the 1990s, scientists have been aware that for the past several billion years, the universe has been expanding at an accelerated rate. They have further hypothesised that some form of invisible energy must be responsible for this, one which makes up 68.3% of the mass-energy of the observable universe. While there is no direct evidence that this "dark energy" exists, plenty of indirect evidence has been obtained by observing the large-scale mass density of the universe and the rate at which is expanding.

But in the coming years, scientists hope to develop technologies and methods that will allow them to see exactly how dark energy has influenced the development of the universe.

One such effort comes from the U.S. Department of Energy's Lawrence Berkeley National Lab, where scientists are working to develop an instrument that will create a comprehensive 3D map of a third of the universe so that its growth history can be tracked.

Known as the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI), this project plans to start with the present day, pinpointing the locations of galaxies in the universe, and then work backwards into the past. DESI officially kicked off with the recent delivery of two new and improved lenses to the Mayall Telescope at the Kitt Peak National Observatory in Arizona.

The first of six such upgrades, these two new lenses – Corrector Lens 1 and Corrector Lens 4 (C1 and C4) – have been in production since early 2015. Measuring 1 meter in diameter and weighing 201.395 kg (444 pounds) and 236.775 kg (522 pounds), respectively, these lenses are scheduled to undergo a final antireflective coating before being integrated into the Mayall telescope's new steel corrector barrel.

The C4 lens after it arrived at the NOAO. The faces of Gary Poczulp, Ron Probst, Dick Joyce and Ming Liang (project scientists for DESI) are reflected in the lens. Credit: Tim Miller/LBL

Each of these lenses comes equipped with 5000 optical fibers, similar to kind of cables used for high-speed data traffic (i.e. internet and telecommunications).

They will give the 4-meter telescope a very wide field of view and be able to detect the light coming from 5000 galaxies at a time. This light will then be directed to the 30 cameras and spectrographs that are connected to the Mayall telescope, which the science team will then measure to gauge its redshift.

For many years, the Berkeley Lab has been measuring the redshift of distant galaxies – the ratio of the wavelength that is seen to the wavelength the light had when it left the galaxy – to gauge their distances from our Solar System.

However, since light will stretch exactly the way the universe stretches, these measurements have also been giving the Berkeley scientists an idea of how the universe is expanding.

Once the entire DESI package is assembled – which is expected to happen by 2018 – it will begin collecting spectrographic information on a total of 35 million distant galaxies and quasars. This information will then be used to construct the largest 3D map of the universe, one that spans 10 billion light years.

This will allow DESI scientists to not only survey the large-scale structure of the universe, but also look back in time and see how the universe changed over the past 10 billion years.

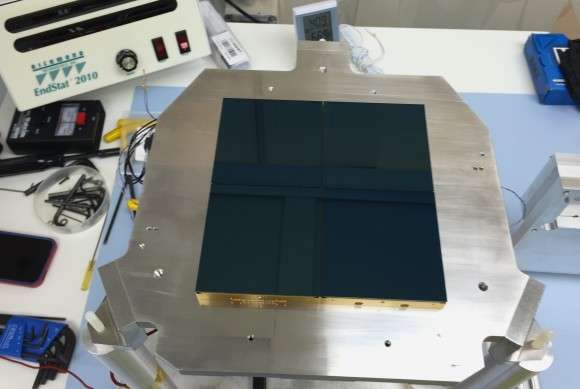

A picture of the Berkeley Lab-developed charge-coupled devices (CCDs), light-sensors that allow the Mosaic-3 camera to capture infrared light from distant galaxies. Credit: Tom Hurteau/Yale University Physics Department

However, redshift alone can only provide astronomers with relative distances. In order to create the 3D map with a genuine sense of scale, the DESI scientists will also be relying on baryon acoustic oscillations – which are periodic fluctuations in the density of the visible baryonic matter of the universe.

Together, these measurements of the changing distance between galaxies could show us exactly how dark matter influences cosmic expansion.

DESI is undeniably the next wave of innovation when it comes to how we observe the universe, combing high-performance optics with computer-assisted analysis. And when the map is finally complete, scientists may begin to see exactly how this mysterious energy that permeates our universe has influenced its expansion and evolution.