IDTechEx asks if electronics manufacturing can join the digital age

Asked whether electronics is a ‘digital technology’, almost everyone would reply in the affirmative. However, while printed circuit boards (PCBs) enable digital technologies, the manufacturing processes used to produce them are still largely analogue.

‘Digital manufacturing’ refers to any method that is directly controlled by a computer – simply using software in the design process doesn’t count. Well-known examples are CNC (computer numerical control) machining, a subtractive method in which a rotational cutting tool selectively removes material, and 3D printing, an additive method that involves selective deposition of metal, plastic, or even ceramic.

In both cases, direct computer control means that every part produced can have a different design and even that the design can be adjusted once manufacturing is in progress.

In contrast, conventional PCB manufacturing takes an analogue approach. The desired pattern is transferred to a mask that is used for photolithography. Regions of material, typically copper laminate on a PCB, that are not coated with the patterned resist are then removed with an etchant. While this approach enables efficient high-yield production, introducing digital manufacturing methods would bring additional benefits.

Why do we need digital electronics manufacturing?

Arguably, the main benefit of digital over analogue manufacturing is that every item can be different with no additional setup time or costs. This is why inkjet printers (digital) are used at home since only a single copy is typically needed, whereas offset printing (analogue) is used for mass-produced newspapers.

With electronics, digital manufacturing enables rapid prototyping, accelerating the design process. It facilitates mass customisation, where every circuit has a different design if desired without dramatically increasing production costs. Furthermore, high-resolution digital manufacturing methods can be used in conjunction with conventional photolithography to repair any unwanted circuit breaks.

Digital manufacturing methods for electronics

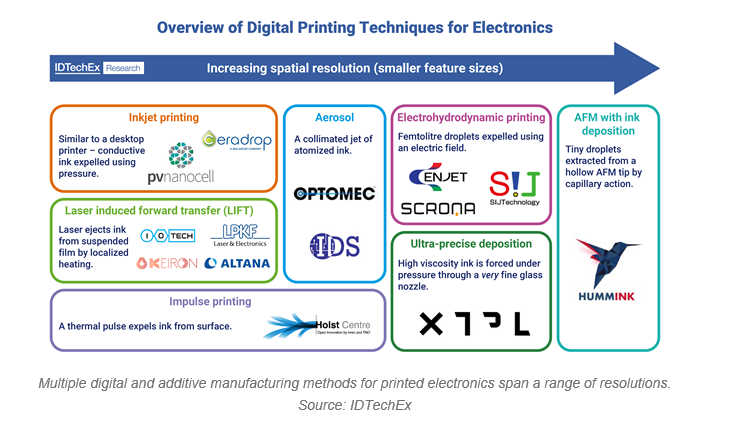

Interest in digital manufacturing methods for electronics has increased rapidly over recent years. While inkjet printing is by far the best-established method of digitally depositing conductive ink, there are a variety of emerging techniques that are both digital and additive. They all offer the direct control of digital manufacturing while spanning a range of throughputs, resolutions, material viscosity, and substrate dimensionality.

Print-then-plate utilises inkjet printing of a thin layer of silver nanoparticle conductive ink to selectively pattern the substrate. This ‘seed layer’ is then fully metalized by electroless plating, producing a copper circuit. This method is already used for mass production. It combines the customisability of digital manufacturing, the reduced waste of additive manufacturing, and the conductivity of copper metal (rather than printed conductive ink).

Laser induced forward transfer (LIFT) can be regarded as a hybrid of laser direct structuring (LDS) and inkjet printing. Briefly, a laser heats conductive ink coated underneath a ‘transfer plate’, with evaporating solvent ejecting the ink. The lack of nozzle is a major benefit since it enables viscous inks typically used for screen printing to be used. There is potential for LIFT to be used in tandem with R2R production, enabling rapid, cost-effective production of customised circuits.

Aerosol printing is a relatively established technique that is well suited to printing onto 3D surfaces. A low-viscosity ink is atomised and formed into a thin collimated jet within a gas sheath layer, enabling resolutions as fine as 10um with a working distance of up to 5cm. It’s already being used in the semiconductor packaging production process and will soon be applied to larger area conformal surfaces such as automotive glass.

Electrohydrodynamic printing (EHD) uses an electric field to ‘pull’ ink from a nozzle rather than relying on pressure to ‘push’ out the ink. Capable of traces as narrow as 1um, this technique is currently being used to repair defects in TFT backplanes. An emerging approach is to combine hundreds of individually addressable nozzles within a single MEMS (micro electromechanical system) chip promises to break the resolution/throughput trade-off for small-scale additive electronics manufacturing.

Impulse printing is an innovative technique in the early stages of development that promises high throughput printing onto 3D surfaces, such as the edges of glass backplanes or 2.5D semiconductor packaging. The approach utilises a rapid heat pulse from a controllable array of heating elements to expel ink from a flat ‘transfer surface’ onto the target object. Since no nozzle is used, ink can simultaneously be expelled from across the heated ‘transfer surface’.

Comprehensive overview

The digital electronics manufacturing methods outlined are predicted to gain further traction, driven by a desire for greater customisability, shorter product development cycles, and demand for 2.5D/3D electronics. IDTechEx’s report, ‘Manufacturing Printed Electronics 2023-2033’, builds on 20 years of covering printed and flexible electronics to explore these technologies and many others, including roll-to-roll manufacturing.

Drawing on information from conference attendance and primary interviews, it outlines the players, capabilities, trends, and requirements across the printed electronics manufacturing space, helping to support choices in product development and when scaling up to mass production.