Architecture solves combinatorial optimisation problems

It has been announced that Fujitsu Laboratories has collaborated with the University of Toronto to develop a computing architecture to tackle a range of real-world issues by solving combinatorial optimisation problems, which involve finding the best combination of elements out of an enormous set of element combinations.

This architecture employs conventional semiconductor technology with flexible circuit configurations to allow it to handle a broader range of problems than current quantum computing can manage. In addition, multiple computation circuits can be run in parallel to perform the optimisation computations, enabling scalability in terms of problem size and processing speed. Fujitsu Laboratories implemented a prototype of the architecture using FPGAs for the basic optimisation circuit, which is the minimum constituent element of the architecture, and found the architecture capable of performing computations some 10,000 times faster than a conventional computer.

Through this architecture, Fujitsu Laboratories is enabling faster solutions to computationally intensive combinatorial optimisation problems, such as how to streamline distribution, improve post-disaster recovery plans, formulate economic policy, and optimise investment portfolios. It will also make possible the development of ICT services that support swift and optimal decision-making in such areas as social policy and business, which involve complex intertwined elements.

Background

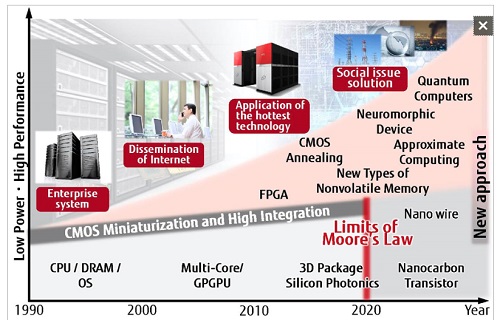

In society, people need to make difficult decisions under such constraints as limited time and manpower. Examples of such decisions include determining procedures for disaster recovery, optimising an investment portfolio, and formulating economic policy. These kinds of decision-making problems - in which many elements are considered and evaluated, and the best combination of them needs to be chosen - are called combinatorial optimisation problems. With combinatorial optimisation problems, as the number of elements involved increases, the number of possible combinations increases exponentially, so in order to solve these problems quickly enough to be of any practical utility for society, there needs to be a dramatic increase in computing performance. The miniaturisation that has supported the improvements in computing performance over the last 50 years is nearing its limits (Figure 1), and it is hoped that devices will emerge based on completely different physical principles, such as quantum computers.

Figure 1

Issues

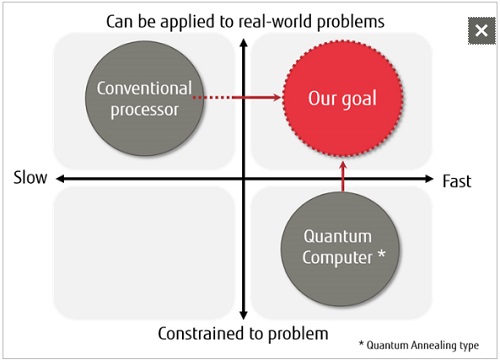

Conventional processors have a great deal of flexibility in handling combinatorial optimisation problems because they process these problems using software, but on the other hand, they cannot solve them quickly. Conversely, current quantum computers can solve combinatorial optimisation problems quickly, but because they solve problems based on a physical phenomenon, there is a limitation of only adjacent elements being able to come into contact, so currently they cannot handle a wide range of problems. As a result, developing a new computing architecture that can quickly solve real-world combinatorial optimisation problems has been an issue (Figure 2).

Figure 2

About the Technology

Using conventional semiconductors, Fujitsu Laboratories developed a computing architecture able to quickly solve combinatorial optimisation problems. This technology can handle a greater diversity of problems than quantum computing, and owing to its use of parallelisation, the size of problems it can accommodate and its processing speed can be increased. Key features of the technology are as follows:

1. A computing architecture for combinatorial optimisation problems

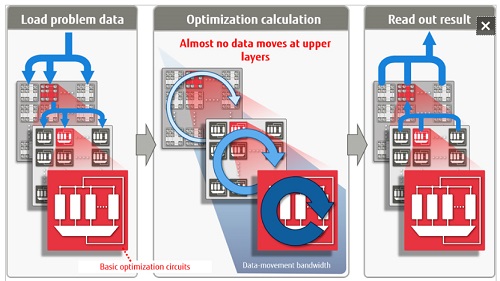

The architecture uses a basic optimisation circuit, based on digital circuitry, as a building block. Multiple building blocks are driven, in parallel, in a hierarchical structure (Figure 3). This structure minimises the volume of data that is moved between basic optimisation circuits, making it is possible to implement them in parallel at high densities using conventional semiconductor technology. In addition, thanks to a fully connected structure that allows signals to move freely within and between basic optimisation circuits, the architecture is able to handle a wide range of problems.

Figure 3

2. Acceleration technology within the basic optimisation circuit

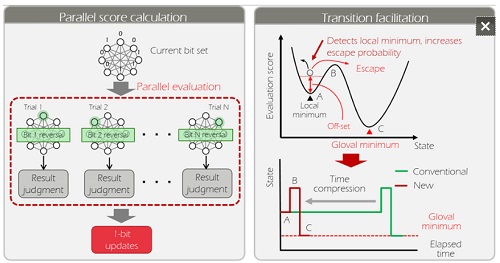

The basic optimisation circuit uses techniques from probability theory to repeatedly search for paths from a given state to a more optimal state. This includes a technique that calculates scores for the respective evaluation results of multiple candidates at once, and in parallel, when there are multiple candidates for the next state, which increases the probability of finding the next state (Figure 4, left). It also includes a technique that, when a search process becomes stuck as it arrives at what is called a "local minimum," it detects this state and facilitates the transition to the next state by repeatedly adding a constant to score values that increases the probability of escaping from that state (Figure 4, right). As a result, one can quickly expect an optimal answer.

Figure 4

Results

Fujitsu Laboratories implemented the basic optimisation circuits using an FPGA to handle combinations that can be expressed as 1,024 bits, and found that this architecture was able to solve problems some 10,000 times faster than conventional processors running a conventional software process called "simulated annealing." By expanding the bit scale of this technology, it can be used to quickly solve computationally intensive combinatorial optimisation problems, such as optimising distribution to several thousand locations, optimising the profit from multiple projects with a limited budget, or optimising investment portfolios. It can also be expected to bring about the development of ICT services that support optimal decision-making at high speed.

Future plans

Fujitsu Laboratories is continuing to work on improving the architecture, and, by fiscal 2018, aims to have prototype computational systems able to handle real-world problems of 100,000 bits to one million bits that it will validate on the path toward practical implementation.