Making provisions for cyber security

As the level of connectivity in our everyday lives increases dramatically, we are never far away from another headline of a vulnerability found in a baby monitor or an autonomous car having been driven into a ditch following a hack. This has increased the need for greater provisions for cyber security.

In addition, for obvious reasons, COVID has driven a huge demand in connected devices in order to limit human interaction. So, we’re living in an age of increased connectivity, particularly in the home. However, some of these devices have now been around for over a decade and as such, have very poor security.

Several years ago the Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS), along with the UK National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) and European partners, deemed that the industry, unfortunately, is failing to get a grip on baseline security, and as such took action to address the issue.

The result is the ETSI EN 303 645 IoT security standard, which establishes a security baseline for internet connected consumer products and provides a basis for future IoT certification schemes. Electronic Specifier spoke to Alex Leadbeater, Cyber Security Chairman at The European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI), to find out more.

Discussing the standard Leadbeater commented: “It’s the first European, and arguably global attempt, for consumer IoT to raise the bar. It is underwritten by the Cyber Security Act in Europe, which highlights to the industry the need for secure products in Europe and protected personal data. So, if GDPR wasn’t enough, here’s another incentive for products to be secure within the European marketplace.”

He explained that the new standard represents a definitive line in the sand and sets a minimum set of security requirements when selling products in Europe. Within that are 13 basic provisions, however, there has interestingly been some pushback on one or two of those, because certain low cost or cheap devices may not be able to meet all 13 provisions.

“A significant part of the consumer IT sector is at the stage where the Windows OS type environment was nearly 20 years ago, when the PC industry went through a very painful phase in the late 1990s where IT security was pretty shocking,” added Leadbeater

“I would also argue a lot of the mistakes people are making in terms of basic IT security are actually the same mistakes people were making two decades ago. Therefore, the tools and skill sets needed to fix it already exist – we just need to think about how to design products to be secure by default, and not designed with security as an afterthought.”

Legacy lethargy

Historically, some product manufacturers have taken the view that because their products don’t really process data, security is not a design consideration. Alternatively, some have taken the view that the devices they produce are cheap and security costs money.

What the Cyber Security Act and the Radio Equipment Directive, combined with GDPR in Europe does, is shift that position. Therefore, evidence is starting to stack up towards mitigating bad design and the EN standard provides a baseline for this.

Companies such as Bosch, British Telecom, HP, Huawei, IBM, Philips, and Samsung have endorsed and contributed to the standard, however, they are competing with cheap, inferior, non-European imports that have not gone through the same design effort and are therefore able to undercut the European products.

And herein lies the issue, as Leadbeater explained: “Consumers generally don't pay for security. If you see two products on the shelf - one with good security, but the other with glossy attractive packaging which is cheaper, consumers will traditionally go for the latter. They are unlikely to look on the back to see if the product is European cyber secure.”

Therefore, the standard is all about achieving a certain base level security standard. The EN standard consists of 13 basic requirements, which then drill down into 68 provisions, 33 of which are mandatory and 35 recommendations.

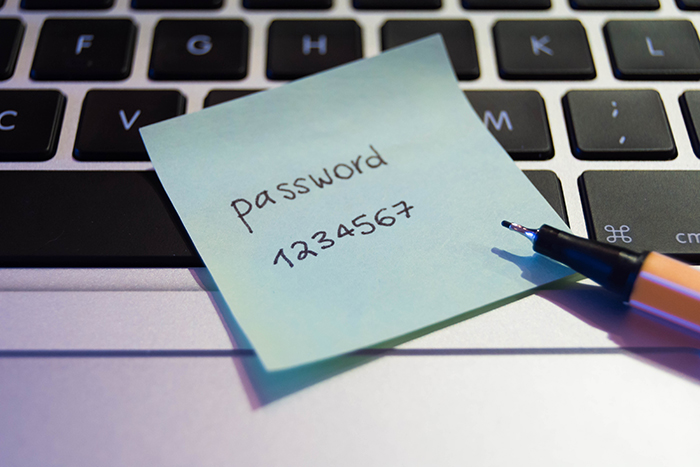

Above: Many IoT devices manufactured remotely from the consumer don't have much of a user interface, and therefore, setting up a unique passowrd can be far from simple

“I would challenge manufacturers to ignore the bulk of those 35 recommendations,” said Leadbeater. “They’re not unreasonable – and if a manufacturer had a product that only met the 33 mandatories and decided not meet any of the 35 recommendations, then that’s not going to be a very secure product. And if it’s consumer IoT in the home, you’re going to need to meet all 68 in order for it to be secure.

“What you can expect over time is that there will be later versions of the document. So in another two to three years’ time, we will look to raise the bar and take that minimum level a bit further. It will be an evolution.”

Indeed, Leadbeater explained that there is a certain amount of concern from manufacturers as some products are nowhere near where they need to be in terms of their basic cyber security and design. Therefore, there will undoubtedly be an implementation timescale which is reasonably achieved within a design cycle or two. Rome wasn’t built in a day as they say, and if too much is asked too early, then the uptake is likely to be poor.

“There is a balance between the reasonable ability of industry to meet the provisions and the level we set the provisions at,” added Leadbeater. “It’s for the EU institutions, ETSI, industry and the Government to come together and establish how fast that is improved. But clearly, it is not a one-step activity.”

Provision examples

One simple provision cited by Leadbeater is no universal default passwords. This is one of the biggest killers for things like Bluetooth pins, and some of the baby monitors and similar products where flaws have been found. However simple it seams, Leadbeater added that it is quite difficult to overcome for IoT devices.

“Unlike a laptop, which you buy from a shop, take home and set up all the Windows installations including your own passwords, an IoT device manufactured remotely from the consumer doesn’t have much of a user interface. So, manufacturers actually have a challenge here.” Solutions to this issue need to be designed in - it can’t be retrofitted as that would create a supply chain issue and devices cannot be managed in the field.

Another example would be the means to report vulnerabilities. “I have a statistic from the IoT Security Foundation that took place on 17th March,” Leadbeater explained. “Only a limited number of manufacturers currently allow vulnerability reporting. So, if you find a vulnerability in your product as a home user, only 13% of the products on the market have the functionality to report back to the manufacturer if a fault is found.”

There are mechanisms in place to deal with breaches in IT or banking for example, some of which are automatic. If your IoT heating controller has just done something unexpected, and you find 200 pints of milk have been ordered for your smart fridge, there has clearly been a security breach, however, for the vast majority of products there’s no way of doing anything about it other than turning the product off.

Leadbeater added: “We had a conference in Brussels run by The European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA), the European security organisation arm of the EU. There was an audience full of IoT providers and big industry, and I asked who had got a vulnerability disclosure scheme, or ever heard of one? I got a room full of blank faces and everybody looking a bit uncomfortable. But that is the reality. So we need to do better as an industry.”

Another key provision is to keep software updated. In the majority of cases home IT equipment is patched, in some cases multiple times a week, and regularly updated. On the other hand, with consumer IoT devices, they are purchased, plugged in and will probably still have the same firmware when the device is decommissioned several years later.

Above: Only 13% of the products on the market have the functionality to report back to the manufacturer if a fault is found

“Software is going to have vulnerabilities,” Leadbeater continued. “Even if it’s secure today, new vulnerabilities, compromises or attack techniques will appear tomorrow. If you have a consumer IoT device that is in a non-security critical role, or is hidden behind a gateway, some of those devices might be tolerable. However, if you’ve got all of your home devices connected directly to the public internet, and they’ve all got insecure software, you’re going to get a compromise of personal data.” Leadbeater added that this also increases the risk of botnets, where attackers infiltrate IoT devices and repurpose them to do something malicious.

“So, it’s all about achieving that minimum baseline,” Leadbeater added. “It’s been really well received both from the consumer organisations, EU institutions, the Government and big European industry, who have all got behind this.”

He stressed that for the manufacturers out there that are selling cheaper insecure products, it’s not that security is unimportant, it’s that they’ve not been incentivised to adopt it before. Large volume products will always be produced for the least cost, driven by market requirements. If security is not a mandatory market requirement, then sadly, in the low cost end, it’s not going to be a priority.

Out with the old?

This raises the question of what to do with legacy devices. What of all the products that don’t meet the requirements that are already on the market or littering people’s houses? You can of course encourage manufacturers to try and produce software updates for old devices (if they’re capable of being updated), however, clearly some are not.

Leadbeater continued: “Even if every manufacturer said that they are going to implement all 68 provisions tomorrow, realistically, that would only refer to products that are currently in the design cycle. Those are not going to appear on the retail shelf for quite a while. And clearly there will be products that don’t meet the provisions that are already in the market place and will remain there for some time (probably appearing for resale on eBay).

“So, this is not an instant fix panacea, this is a longer term investment – but security always is. Security improvements today are about bigger gains in the longer term. Security is not and never will be, a short term, ten minute investment.”