Modern manufacturing demands drive growing reliance on factory software tools

OEMs and contract assemblers are constantly seeking a technological edge over their competitors, investing in better, more modern machines, to win new business and grow their market share. A high level of automation is now applied at each point in the surface-mount assembly flow, from program generation through solder-paste deposition, component placement, inspection, reflow and test.

Contributed by Yamaha Motor IM.

On the other hand, production planning is still often regarded as a fundamentally manual affair. Although software tools are available to help assign work orders efficiently to utilize capacity and minimize changeovers, and to help manage production as it happens on the factory floor, some manufacturers are not taking full advantage of their power. Times are changing, however, and the assistance of software tools is becoming increasingly important to help assign work orders efficiently, utilize capacity, and improve productivity.

Market Demands Drive Manufacturing Changes

Today’s manufacturing businesses must be ultra responsive to market demands. Product lifecycles are becoming shorter, first-to-market advantage is critical, customers often demand a broad choice of product variants, and individual customisation is often expected. At the same time, manufacturers increasingly seek to build to order, and so minimise unused inventory and associated costs. As a result, lot sizes are becoming smaller and assembly activities are increasingly moving towards high-mix and mid-to-low-volume. In the past, a large site could be making a few different types of products in large volumes of several thousand or tens of thousands at a time; today, the same factories could be building hundreds of product types, in small batches, using many thousands of different component part numbers.

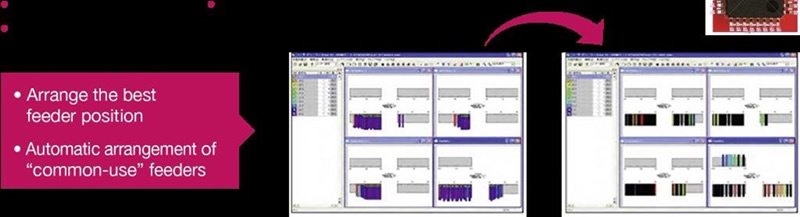

In this business environment, production-planning responsibilities such as assigning work orders optimally to balance the load across machines and lines, minimize changeovers by arranging feeders optimally (figure 1), and ensure that the required number of components are available for the right feeders at the right time are increasingly difficult to handle using human brainpower alone. Time pressure is an important factor here: since the plan is determined according to the current status of resources – such as capacity requirements of all upcoming projects, delivery dates for the various products, and component inventory available – the production plan must be completed and actioned quickly.

Figure 1. Distributing jobs, grouping, and optimizing feeders are increasingly complex and best handled using automated software tools.

Software-Assisted Planning and Management

The role of high-quality offline software tools that aid with planning and line balancing is set to become more important to the assembly businesses of the future. Manufacturers may choose third-party software to help assign work orders, group products on lines to allow optimal feeder and component assignment with minimal changeovers, and balance the work to make best use of available capacity. This approach can appear sensible, particularly if the various machines in the line are from different vendors and thus require a neutral software executive capable of interacting with all machines equally.

On the other hand, a unified approach based on key items of equipment and overseeing software from the same vendor can deliver advantages. Yamaha’s P-Tool, which is part of the Yamaha Factory Tools suite, is fine-tuned to exchange data efficiently with Yamaha printers, dispensers, mounters and inspection stations in the SMT line. Essential processes for product preparation, such as CAD-data conversion and reverse gerber engineering, for example, produce programs that are ready to run on the machines with minimal additional manual fine-tuning. Moreover, features of the software such as the visual editor, which supports program verification, is designed using intimate knowledge of the machine features and capabilities. The programming features for optimization and balancing, also, take into account the individual features of the machines, such as the sizes and movement of placement heads or nozzles, to avoid interference and create programs that are right first time.

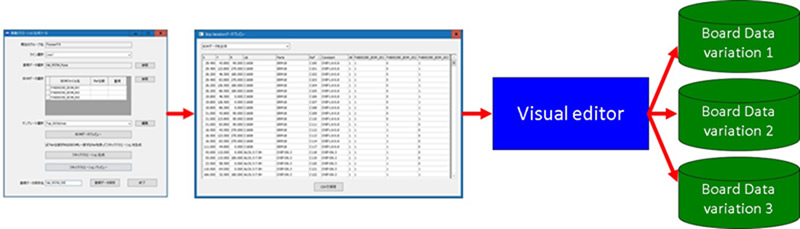

Because software-assisted planning will take an increasingly important role in the SMT lines of the future, Yamaha continues to develop and extend the features of P-Tool and the entire Factory Tools suite, to deliver the capabilities tomorrow’s manufacturers will need. In addition, users can extend P-Tool with extra Pioneer Options utilities, which include features such as fast automated generation of precision board data from gerber data, board images or CAM files such as ODB++, GenCAD, or FABmaster. In addition, a new mounting-variation creator responds to manufacturers’ need to build multiple versions of a common base board, by automatically importing multiple bills of materials (BOMs) and managing mounting variations for up to 254 variants of one board (figure 2).

Other packages with in the Factory Tools suite help to verify machine setup and manage materials and components including LED binning (S-Tool), and support traceability and reporting down to individual component level (T-Tool).

Figure 2. Automated handling of board variants based on one set of master data relieves manual data-creation and management challenges.

Monitoring Status in Real-Time

While software-assisted planning is essential for consistent on-time delivery and cost-effectiveness, managing each build as it happens on the line brings a different set of challenges. Operational efficiency and process control are critical, to complete work orders on time and maximize end-of-line yield. Coordinating the execution of large numbers of work orders, often for small batch sizes, distributed across multiple SMT lines challenges traditional production management techniques that rely on local machine monitoring and tower beacons. Production managers need quick updates on the status of individual jobs, and to be ready when feeders need replenishment or changeovers are due.

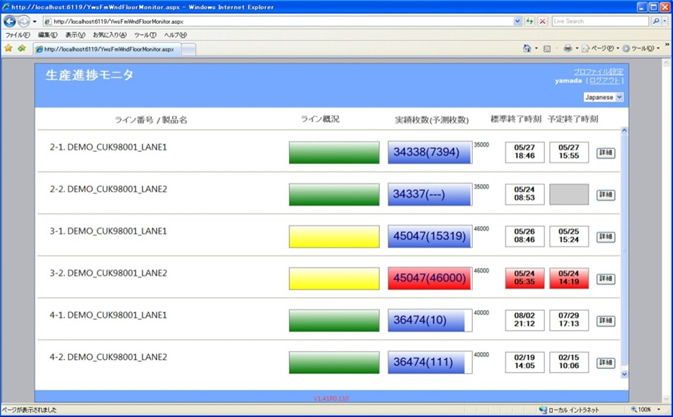

Monitoring software can provide the required information at a glance, via a convenient graphical interface. Colour-coded indicators (figure 3), such as those presented by tools such as the Yamaha’s M-Tool monitoring software allow operators to quickly assess the status of each line and intervene instantly in the event of exceptions or stoppages. In addition, live timing information shows operators exactly when a current job will finish, allowing them to prepare everything that will be needed for the next changeover. Parts-remaining counters help keep all lines working continuously by giving advanced warning when feeders need to be replenished.

Figure 3. At-a-glance status indicators help manage a high product mix spread across multiple SMT lines.

By gathering all this data electronically, monitoring software also gives manufacturers unprecedented opportunities to analyse activities and organization on the factory floor. Statistical analysis can provide visibility of trends and events, identify and fix recurring errors, and set targets for continuous improvement.

Closing the Loop

To ensure optimum productivity and end of line yield, and minimum waste, any assembly defects arising from problems with individual machines need to be identified as soon as they occur and fixed immediately. This can be done effectively using closed-loop feedback of inspection data. Software that automatically compares inspection alerts with data showing the machine, feeder and nozzle responsible for placing each component can pinpoint in real-time the exact cause of any defect, and guide the operator to solve the problem.

Yamaha’s QA Option software does this by comparing No-Go (NG) alerts generated by its YSi inspection stations with the parts list for each mounter. If a match is found, the machine concerned is stopped and QA Alert reports the location and nature of the defect. If inspection is performed immediately after components are mounted, before reflow, a problem such as a blocked nozzle or jammed feeder, or a printer problem such as incorrect stencil alignment or blocked aperture, can be rectified after only a small number of boards have been populated.

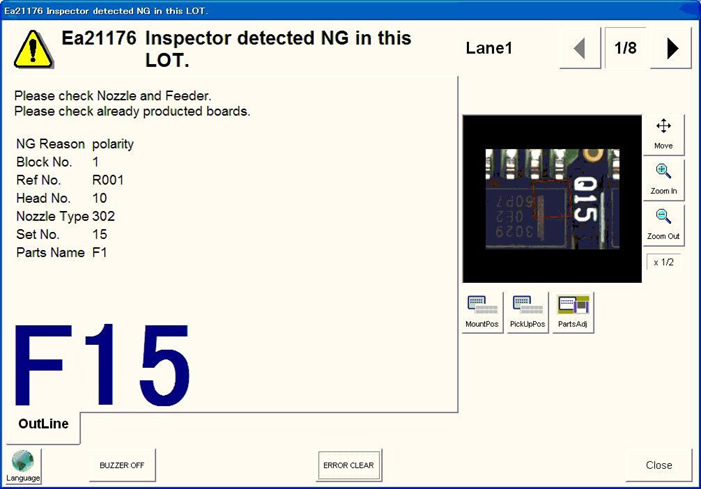

Figure 4 shows how QA Option provides the information an operator needs to rectify an error that has caused a populated board to fail inspection. In this example, a polarity error has been traced back to a dual-lane mounter. The report is presented on the mounter, and shows the fault type, component, location on the board, nozzle details and the lane concerned. Using this information, the operator can quickly identify the cause of the defect with minimal further investigation needed. This allows the line to be returned to full operation very quickly. The information from the QA Option report can also be sent directly to the operator’s mobile, to help resolve exceptions as quickly as possible.

Figure 4. The QA Option error report guides the operator directly to the cause of the AOI NG flag.

Another aspect of this software permits mounters to feed information forward to the AOI station to help maximise productivity of the line. A mounter can notify AOI immediately after a tray or feeder has been changed, for example. This ensures the AOI will verify the component identity at the part location concerned, using optical character recognition, for the first few boards after the change. If the identification is satisfactory, the AOI can subsequently revert to its normal program allowing the line to return to full-speed operation.

Conclusion

As the challenges of modern surface-mount electronics manufacturing continue to intensify, planning, scheduling and line monitoring are becoming too complex for human brain-power to manage unaided. Software tools to help with these processes have been available for some time, and have evolved powerful features that are easy to use via graphical interfaces and guide the user to complete each task to a high standard, quickly.

As more and more assemblers are required to handle larger numbers of products, smaller batch sizes, shorter turnaround times and tighter market windows, this type of software is transitioning from an optional extra to an essential for business.